Disappointment. A simple, 14 letter, polysyllabic word hiding mountain ranges of experiences each one of us has had to deal with many, many times. Not so?

The first time disappointment made a lasting impression on me was when I was 13. I had just returned to rugby after being concussed by a big, robust winger called Caesar Merrifield – from the Eastern Cape I seem to remember – who ran over my attempted tackle from my full back position. I remember hearing a big bang crash in my head but felt no pain. I woke up, flat on my back, with a circle of anxious adult faces peering down at me and our coach, the late John Ince, helping me to my feet and arranging for one of the parents to drive me home.

It was short break on a Friday and all of us young rugby players clustered around the notice board to look up the team selections for the next day’s matches against other schools. I discovered I had been unceremoniously dropped to the B team. It was the first time since I started to play rugby at the age of nine that I had been dropped from the A team. No warning or reason had been given but I suspected that it was because my tackling was no longer what it had been. I was nervous of a concussion action replay and occasionally fluffed a tackle or, worse still, contrived to miss one. Nevertheless, I remember my cheeks burning with embarrassment as I stood next to the board.

Worse was to follow, however, and the next year I was dropped to the C team and moved from fullback to fly half. It was humiliating and a humiliation which endured for that entire year and the next.

When I was 15, a number of things changed. For starters, I was much bigger, faster and took pride in the fact that I was acknowledged as a good tackler. I was also determined to improve my game and did so under the coaching of a teacher who was invested in us boys and the game. Despite the vociferous objections of the father of the boy I ultimately replaced and the boy himself, I regained my spot in the under 16 A team and remained there for the entire season, although now playing either centre or wing. It was a year of making amends, on the rugby field at least, and my father, an ex-first league flanker in his day, even came to watch one or two games.

The original disappointment faded into obscurity but I never forgot it. It was a hard lesson learned and I carried the saying, “Pride comes before a fall” on my hard drive ever after.

I was just out of articles of clerkship, a two-year period of legalized slavery invented by attorneys in South Africa to provide them with all but free labour by eager, newly qualified law graduates under the guise of teaching them the practical aspects of practicing law in the real world.

Some law firms actually did try and train their young graduates but many abused them by requiring them to perform menial tasks like collecting partners’ dry cleaning, fetching their children from school and queueing for tickets to the next rugby test match. The fact that the firm I slaved for more than doubled my salary the month after I passed the law society bar exams and completed my articles, is a small measure of how much they had profited at my expense. I was also made an associate in the firm, one big step down from the coveted status of partner.

At this time, a past fellow law student friend kindly recommended his businessman brother-in-law to me and so started a relationship with he and his two partners that culminated, years later, in me advising them on a major acquisition in North America. The fact that it interrupted and ruined a long planned round the world trip on the first leg in Mauritius, the first real holiday in many years which my wife and I hoped to enjoy, was incidental. I was only too delighted to help, felt I had become an integral part of their senior executive team and could look forward to many new international legal instructions.

How wrong I was. Within weeks of successfully closing the very complicated deal involving companies in many parts of the world, I was unceremoniously fired, again withou

t warning, rhyme or reason and replaced by a lawyer in a well-known tax haven. The disappointment haunted my nights for many weeks and, long after I left law for business, there were times in the early hours of the night that I thought about my dismissal and wondered what I could have done better or differently to have avoided the unceremonious sacking. To say I was bitterly disappointed was an understatement.

Somehow, while the selection to the under 16 A rugby team was satisfying and my reasonable successes as a lawyer and businessman equally so, the latter never quite compensated for the original disappointment, and I have often wondered why. I think the disappointments were so unexpected and, in my humble opinion, unwarranted, on the one hand, whereas the successes were planned and the result of much hard work over time, on the other hand. The former seemed unfair and the latter the reward for hard work, so the latter never quite compensated for the former. But learning to overcome and deal with disappointment, not allowing it to fester and ruin my life but rather act as a motivational force was, I believe, of major importance to my hunting as well as life in general.

It was Ethiopia in January. Our camp was at 13 400 feet in the Kaka Mountains south east of Addis Ababa. Things did not look promising. Our safari outfitter had lost the way three times in trying to find his own base camp.

To say the camp itself was poorly organized would be flattering the camp. The cook burnt hard boiled eggs twice before he was eventually fired; there was insufficient bedding and I slept with all my clothes on in the freezing conditions in an old, threadbare, army tent. There were no showers – the outfitter said it was too cold to shower! Much more importantly, there were no mountain nyala and I had paid the exorbitant trophy fee in advance. There was no refund if you failed to shoot one.

Three weeks later, despite hunting from dawn to dusk every day, I had seen only one small, young mountain nyala bull, which I had been hysterically and repeatedly urged to kill. I had also horseback ridden a day each way to the Kubsa Mountains and back, which I only discovered later was in a concession owned by another outfitter. I had done so at the urging of the preceding recce party who returned from there bearing a stick measuring some 28 inches, which they swore blind was the horn length of the mountain nyala bull they had seen. As I subsequently discovered, this bull and any other mountain nyala in the Kubsa Mountains, had perfected the art of walking on the ground without leaving tracks!

I was bitterly disappointed, not only with the outfitter and his team of misfits – for example, my PH had neither a rifle, knife or binoculars – but with myself. I should have known better. I had not been as thorough as usual in my research into the best area, best time of year and best outfitter but had relied on the advice of a very experienced hunter who had preceded me. Big mistake!

Disappointment is that much harder to metabolise when you know you were partly or entirely to blame for your predicament. In my case, it cost me two years and another safari plus trophy fees. In total, I spent 33 days hunting mountain nyala before I eventually shot a mediocre bull with Nassos Roussos of Ethiopian Rift Valley Safaris and another six days on a second safari with him before I shot one which, although not the biggest bull around, was one with which I was more than happy.

I booked an elephant hunt in Zimbabwe but, a few days into the hunt, was told that the hunter before me had shot my elephant and there was no longer an elephant on quota for me. I was offered a second replacement hunt free of charge but for the cost of the new PH. On the second safari, I failed to find a fresh elephant track. Not that this would have helped much had we done so as, apart from the mind numbing, blistering heat at the end of the season, it thunderstormed every day, usually in mid- afternoon, wiping out whatever fresh tracks there might have been, not to mention the lightning strikes all around us as we carried our metal lightning rods over our shoulders!

The repeated disappointments – it seemed as if my elephant hunting was jinxed – were relatively easy to deal with compared to some of my past ones. The failures had not been expensive, although the time wasted could never be recouped. Still, we hunters are a resilient and optimistic lot and there was always the next hunt, the one that would change things and I knew, even back then, that hard work plus opportunity equaled luck. That it was possible through hard work, while not being able to change your luck on demand, to give yourself better opportunities for luck to play its well-earned part.

On my third elephant hunt, this time in Mocambique, the government cancelled elephant hunting without consultation or warning in mid-season and I was so disappointed until my outfitter kindly bought an elephant license for me in Chewore South, Zimbabwe.

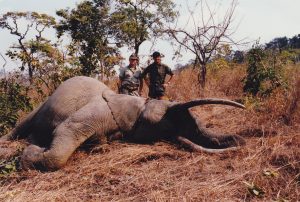

High in the Chewore hill tops, Joe Wright and I spied the bull I had been searching for for over 42 days – a lone, old bull with long elegant ivory – weight was not an issue for me – in the last few years of his life. we clambered down the long, steep, rock strewn slope keeping the bull’s back to us, the light breeze in our favour and I brained the bull with my .460 Weatherby Magnum, customized for me by Bill Ritchie, the well-known gunsmith from Krugersdorp and Vince, his very capable assistant.

I remember asking Joe to back me up as this was my first elephant and I was determined to use the side brain shot. I just felt that such a wonderful animal, on his sixth set of molars and nearing the end of his undoubtedly eventful life, deserved to be killed instantly. If the bull did not fall to the shot, I wanted Joe to shoot it. I did not want this magnificent beast to suffer at all if I could possibly help it. Sounds a bit soft I know but, what can I say? That was how I felt and I saw no reason not to put my feelings into practice.

Joe delegated his role to his brilliant tracker, Magara, with his .458 Lott and, within split seconds of my firing, I heard his rifle fire to my right despite the bull falling in its tracks. When we eventually looked over the carcass, we found Magara had hit the bull in the left buttock from 40 paces!

I was in awe of what I had done and it is true that emotions threatened to overwhelm me. Joe and Magara recognised this and walked off to one side to give me a few moments on my own with this magnificent creature. Any disappointment that I might have carried over from my previous attempts vanished in the rush of emotions that followed the successful conclusion of the hunt.

But the disappointments that accompanied my abortive mountain nyala and elephant hunts were not isolated events. For example, I hunted Lord Derby’s eland for 21 days on two safaris before managing to find one of the iconic, old bulls. Dwarf forest buffalo took 16 brain damaging rain forest hunting days and my first one was a cow that chose me, not the other way around. Forest sitatunga took even longer and I was successful on Abyssinian greater kudu on only my third safari. I can go on and on.

Had I not been taught and learnt how to deal with disappointment, I do not believe I would have succeeded in the hunts for any of the above animals. There is a lovely Afrikaans expression, “Aanhouer wen (the persister wins)”. Anyone can learn to persist. It takes no talent, no intellectual ability or advanced skill, merely a stubbornness, a doggedness, a determination not to give up at the first hurdle.

As the famous Jordan Petersen likes to say, “Life is tough. Deal with it.”